Regardless of what the writer of this screenplay says way after the fact, he knows that what the now deceased permanent A list mostly movie director did care about showing and telling the truth in his final film.

Every little detail of the film has another eye opening moment and the writer is scared to go down that path.

It is just easier to go along with the tide.

Frederic Raphael

Eyes Wide Open: A Memoir of Stanley Kubrick”

Stanley Kubrick

Eyes Wide Shut

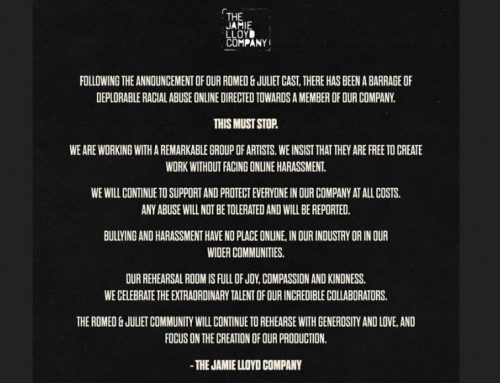

“This is confidential material. Where did you get it?” Frederic Raphael looks back at Eyes Wide Shut

“Je ne cherche pas, je trouve” was Picasso’s retort to a pious inquiry about how he looked for ideas. His use of a set of handlebars to confect a metal goat was a typical example of literal recycling. Henry Moore was inspired by weathered rocks; Tracey Emin by weathered beds. The litter of earlier material disposed Stanley Kubrick, as it did ancient Greek tragedians, to select his subjects from existing sources; Barry Lyndon (1975) – from an 1844 novel by William Thackeray – the least likely, most faithful instance. ‘Make it new’ depends on there being something old.

Eyes Wide Shut is a translation in both time and place: Arthur Schnitzler’s Vienna of the 1880s in his source novel Dream Story (Traumnovelle) became ‘today’s’ New York, constructed at Pinewood. What passed for ‘now’ included ‘then’: the New York City of Stanley’s adolescence. Woody Allen mocked the lavishness of what was supposed to be a young doctor’s Central Park West home, but the dreamy aspect of Schnitzler’s novel sanctioned subjective distortion. The title Eyes Wide Shut was devised, in a blink, by Stanley, after I had proposed ‘Woman Unknown’.

While Stanley incited me to re/present a Viennese marriage in modern dress and dialogue, he reverted, with pious regularity, to what he called “Arthur’s beats”: the movie should honour Schnitzler’s dreamy source. This included, so Stanley insisted for a long time, the ending in which the story’s sleep-walking antihero finds himself awake and back in the conjugal bed.

During more than two years of collaboration, Stanley and I met, always at his barbed-wire fenced compound near St Alban’s, only three or four times, for lunch. No one else was ever present. We never sat down to discuss problems on the script. Our practical conversations, often of an hour or two, were on the phone. After Stanley had studied the pages I had faxed, he would say that he liked this or, as time went on and he became more anxious, did not like that.

Legend promises that, in the 1960s, he had toyed with making an art version of a blue movie with Terry Southern, when they were working on Dr. Strangelove (1963). The closer he came to shooting Eyes Wide Shut, the more anxious he became about how to double the outrageous with the permissible. He scanned whorehouse brochures on Japanese TV in the hope of happening on clues.

Schnitzler’s ‘beats’ did not embrace any account of who organised the orgy. The episode concluded with a manifestly dreamy escape in a horse-drawn cab. I reminded Stanley that the enigmatic ending of Michelangelo Antonioni’s Blow-Up (1966) had not given short measure a good name.

Eventually, Stanley asked for some plausible background for what the orgy’s master of ceremonies, a millionaire whom I called Ziegler (played by Sydney Pollack), regularly organised. One critic has insisted Ziegler’s name was culled from some 14th-century Hasidic rabbi. In fact, I nabbed it from a garrulous agent who represented me in 1969.

In response to Stanley’s request, I typed out several pages of what purported to be an undercover FBI agent’s dossier on Ziegler and his friends. Their sexual extravaganzas were alleged to have been staged in honour of J.F.K.

I faxed my pages to Stanley and was almost instantly called back, in a voice I had never heard before. He wanted me to tell him right away where I got “this stuff”. I said, “From between my ears.” He said, “Freddie, don’t fool around with me. This is confidential material. Where did you get hold of it?” “Stanley,” I said, “I’m a writer. I make things up.” Even provocateurs can dread the knock on the door.

Eventually I convinced Stanley that there should be a final scene with Ziegler which would explain some of the things that had happened in the ‘dream’. He turned down an early version, although he liked it, because “It needs Bogart and Greenstreet and unfortunately I can’t get them, so… would you do it again?”He used to ask the same thing of his actors. He did not know what he was looking for, but – like Picasso – he recognised it when he came across it. – Source

Eyes Wide Shut: Ending, Themes and Symbols Explained

Eyes Wide Shut opens on an image that captures what this film is all about. To the spying viewer, this is clearly an erotic image. Yet, to the woman’s husband who’s theoretically the person observing this view, the sight is mundane, and that’s signaled in the quick, casual nature of the shot.

Everything that follows in the story of the woman, Nicole Kidman’s Alice, and her spouse, Tom Cruise’s Bill, elaborates in the ideas embodied in that opening image.

The focus of Eyes Wide Shut is the scary connection between the erotic and the anonymous. It explores the role that fantasies of strangers play in our sex lives, and it suggests that married people are, ultimately, also strangers to each other.

Stanley Kubrick’s final film was one of his rare box office successes, but it’s among his more underrated works, and that’s perhaps because on first viewing, it’s a little difficult to put your finger on exactly what it’s saying.

If you revisit the film, though (and now is a perfect time to do that, for its 20th anniversary) Eyes Wide Shut is powerfully terrifying. It takes Kubrick’s trademark skill for putting human nature under a microscope, and does that very close to home, peering without bias at the lies that underlie any marriage. – Read more here

Read more on these Tags: Frederic Raphael, Stanley Kubrick