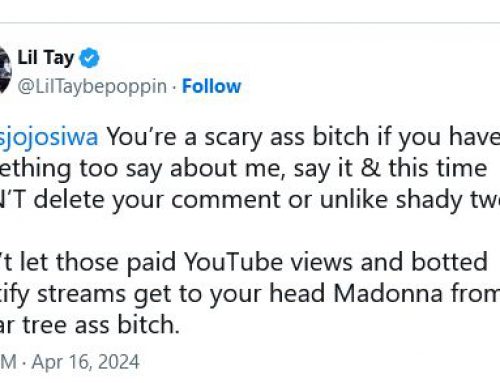

The biggest K-pop boyband preaches about no-violence campaigns and loving yourself at the UN while working with a composer, aged 43, who drugged, raped, filmed young women, and drove one of them to suicide.

His reputation was no secret, but they worked with him on at least four albums.

A member who is a dancer of the band and loves media playing his donations to children charities, made a solo song with the rapist in 2020 despite the composer being charged with rape in 2019.

Their rabid fans are fake woke like the band, so they ignored the news and still continue mass-buying the songs and basically sponsoring the rapist’s lawyers.

BTS

The Dark Side of K-Pop: Assault, Prostitution, Suicide, and Spycams

If K-pop has a spiritual home, it’s probably SMTown. Operated by SM Entertainment Co., the six-story complex in Seoul’s wealthy Gangnam district is a high-tech shrine to South Korea’s most successful cultural export. The lobby walls are covered with framed black-and-white headshots of SM’s “idols,” as K-pop stars are known. By the elevators are hundreds of Polaroid-style portraits of the same artists in a more candid light, albeit with skin so touched up it appears carved from marzipan.

The centerpiece of SMTown is a museum honoring the label’s most prominent groups. There’s an extensive section for Super Junior, a 13-member boy band that was one of K-pop’s first big-ticket acts, and another for Girls’ Generation, a syrup-sweet ensemble that flirted with global stardom thanks to mixed-language tracks such as I Got a Boy. (“I got a boy/ Cool!/ I got a boy/ Nice!/ I got a boy handsome boy!”) There are also several displays for SHINee, a five-member male group. Or rather, a formerly five-member male group. In December 2017, lead singer Kim Jong-hyun died by suicide in a Seoul apartment. “The depression slowly chipped away at me, finally devouring me,” he wrote in a final note. “It wasn’t my path to become world famous. … It’s a miracle that I endured all this time.” Kim was 27; had he been revered in the West, he might have been remembered in the same breath as other megastars, such as Jimi Hendrix and Amy Winehouse, who died at that age. But at SMTown, Kim’s death never happened. An otherwise detailed chronology of the band makes no mention of it; on one side of the relevant date he’s in the photos, and on the other he isn’t.

It wouldn’t be entirely fair to call this a metaphor for K-pop’s core bargain with its audience, but it wouldn’t be completely wrong, either. K-pop depends on a highly controlled relationship with fans. The idol, the genre’s base unit of stardom, is gestated from adolescence through years of grueling training. When he’s ready to meet his public, his labels place him in a group, flowing his image and voice into the music, video, and social media streams of fans across East Asia. The ideal idol has a moral record as unblemished as his pores, eschewing drugs, gambling, and public misbehavior of any kind. While female groups employ the usual male-gaze clichés—the flirty schoolgirl, the doe-eyed ingénue—the frank sexuality of a Rihanna or a Lady Gaga would be unthinkable. And even though many, many K-pop songs are about relationships and breakups, labels often discourage dating. What the music loses in edge, it more than gains in marketability. Korea and Japan are conservative societies in many ways, and China, a nascent market, often bans foreign acts it deems negative influences.

But the wall of virtue collapsed this year, thanks to a scandal that continues to grip the industry. It began in January, after a man said he’d been beaten by guards for trying to stop a sexual assault at Burning Sun, a Seoul nightclub partly owned by Seungri, one of K-pop’s most bankable stars. The claims spiraled into a series of overlapping allegations related to sex trafficking, date rape, spy-camera recordings, and bribery. Seungri and several other idols are under criminal investigation, while the founder of YG Entertainment Inc., the label responsible for K-pop’s first global crossover hit, Gangnam Style, resigned as a result of the turmoil. Prosecutors, meanwhile, opened an inquiry into whether police had been running interference for stars, ignoring reports of sexual assault and allowing venues such as Burning Sun to function as hubs of predatory behavior.

The scandal shone an unflattering light on the idol system, which elevates artists from tightly regimented training schools to stardom in their early 20s with money and fame to burn. It’s also triggered a larger debate about the treatment of women in South Korea, huge numbers of whom face harassment, assault, or surveillance by molka, or spycams, which are routinely discovered in hotel rooms and public bathrooms.

Given K-pop’s titanic cultural and economic significance—the revenue of the four largest K-pop companies in 2018 was about $1.1 billion, according to music export agency DFSB Kollective—a real change in how it operates could shift attitudes in South Korea as a whole. But in a country where social progress often lags behind technological and material advancement, no one is getting their hopes up. For women in South Korea, “it’s a desperate situation,” says Sim Sang-jeung, a lawmaker and former presidential candidate who’s pushed for stronger protections against assault. At Burning Sun, “police and the authorities tried to protect those who have power and conceal crimes,” she says. “In women’s daily lives, nowhere feels safe.” – Source

Read more on these